An interview with Cornelia Kaminski, German pro-life leader

A couple of months ago, the German Federal Joint Committee approved the financing of prenatal blood tests for detecting trisomies, meaning that as of 2022 the test is going to be fully covered by health insurance for every pregnancy. The German Down syndrome community, bioethicists, pro-lifers, and church leaders fear that it will lead to an increase in abortion, with Down Syndrome babies being the primary target. We talked to Cornelia Kaminski about this, and other issues concerning the anti-eugenic and pro-life movement in Germany. Kaminski is the federal chairwoman of the organization Aktion Lebensrecht für Alle (ALfA), the oldest and one of the most prominent of German pro-life organizations.

What is the legal frame for eugenic abortion in Germany, and what is the usual prenatal “screening pathway”?

The abortion law says that, in case the mother is expected to suffer either physical or psychological grievances if she carries the pregnancy to term, she is legally allowed to end the pregnancy at any point up until term. Whereas in former times this indication focused on a handicap of the baby, it now looks at the physical and mental health of the woman. The previous wording was struck down from the law, since many organizations and NGOs fighting for the rights of the people with disabilities were against it, for understandable reasons. Basically, the same practice has simply been given a different name.

Mothers are offered counselling in relation to the diagnosis of the child. This implies dealing with the medical, psychological and social aspects of the diagnosis. Another expert opinion is also required to confirm the diagnosis. Mothers must be handed some information on the diagnosis, and they must be informed about having the right to psychological and social counselling. A period needs to pass between the diagnosis and counselling. This period is at least three days. However, the woman does not have to contact the available counselling institutions, she is allowed to refuse. Also, there is no limit past which you are no longer allowed to abort the child. Abortions for medical reasons are not illegal in Germany, whereas abortions for social reasons are officially against the law but are not punishable if certain requirements are fulfilled.

The official figures on the abortion rate for children with Down syndrome following a pre-natal diagnosis is nine out of ten: every tenth child with Down syndrome survives the prenatal screening pathway in Germany. The usual screening pathway starts with a non-invasive screening blood test in week 9. Not everyone takes this test, because it has not been covered by insurance for all, and younger women usually do not take it because they are not “at risk”. In that case, the screening pathway starts at 12 weeks, when mothers are offered ultrasound, and if something comes up, they are offered an amniocentesis. In any case, amniocentesis is required for a definite diagnosis.

It is important to note that doctors used to be allowed to do as many ultrasounds and fetal imaging as they wanted to. However, as of January the 1st this year, that has been prohibited. Doctors are now only allowed to do an ultrasound if the ultrasound is conducted for diagnostic reasons. The so-called “baby TV” ultrasound has been made illegal. And another change is that midwives are no longer allowed to do the ultrasound. Doctors are now the only persons allowed to do that, and only for diagnostic reasons. This is a set-back for the pro-life community in Germany. Our own organization used to offer ultrasounds, just to show women what their child looks like, but that has now been prohibited.

What is now happening in Germany regarding the introduction of NIPT to the general insurance health care plan?

Two things are now happening in Germany, actually. NIPT is going to be offered to each and every single woman. All of them are going to be told “it’s just a simple blood test, nothing more than that”, and the test is going to be free of charge. And if the test turns out positive, then mothers will be offered the amniocentesis for a definite diagnosis.

Another thing. A couple of years ago, the High Court made a decision which ruled against a doctor in case of birthing a child with a disability. The verdict said that if a doctor failed to advise their patient to undergo specific tests like ultrasound, or did not recommend an amniocentesis, they have to pay indemnities in case a child was born with a disability. This is called “child as a damage” in the legal framework. The doctors are now held accountable. If they failed to warn their patient, they then have to pay for the child’s health care and everything that comes attached with a disability diagnosis. This is the reason why doctors are very eager to inform their patients about all the possibilities for prenatal diagnosis. It has become very difficult to refuse this.

What can we expect after this introduction and how are pro-life organizations, specifically Aktion Lebensrecht für Alle e.V., addressing this issue?

Well, what we can expect is that even less children with Down syndrome will be born. Second, there will be a lot less tolerance for parents who welcome children with Down syndrome, because they are now so “very easily avoidable”. I also fear that sometime soon, health insurance companies will begin to refuse insurance to children with Down syndrome, leaning on the fact that NIPT is now covered by insurance. They would just refuse to insure the child, because if the child was screened out, they would not have to pay for its health care. And since we know that children with Down syndrome tend to have a couple of health issues that other children don’t have as easily or as often, insurance companies will try to avoid that.

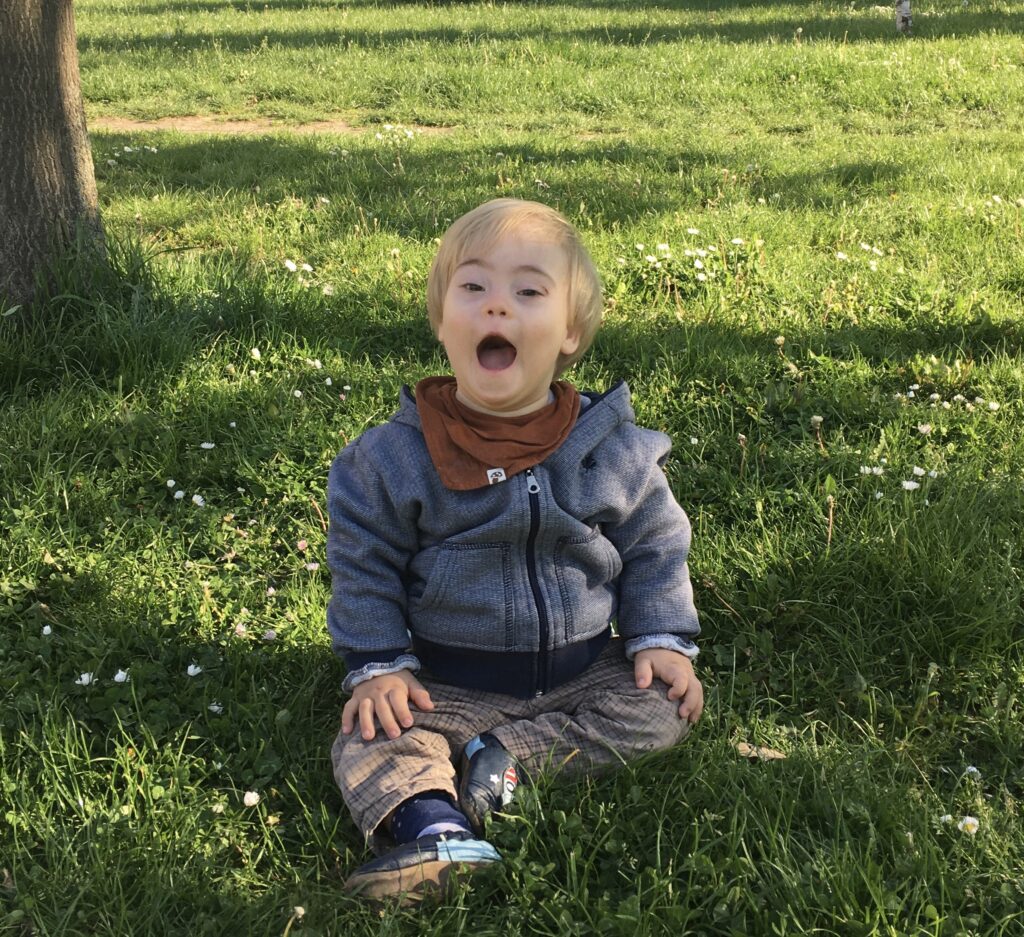

This is precisely what we are going to draw attention to, as a pro-life organization. The inclusion of NIPT into insurance is going to have grave consequences on equality and we are going to warn people about these consequences. Also, we will continue in raising awareness about the beauty of the existence of children with Down syndrome and the wonderful way they can live their life. We will insist on the fact that people with Down syndrome enrich our society. Frankly, we’ve lost the battle with NIPT and raising awareness is the only thing we can do now, really: to encourage women who receive the diagnosis not to abort their children. We also have a doctor we work with, and whom we recommend to women in this situation. He is a specialist in the field of Down syndrome and works with children with disabilities. We will continue providing information to the public, and we will also continue with our efforts in social work.

Photo: Demo für alle